Intelligence and diplomacy need each other, but this interaction is not always without friction. What then unites and distinguishes intelligence and diplomacy? The aim of this post is to identify synergies and areas of risk at a time when global audiences have been openly briefed about Russia and its war against Ukraine.

Intelligence and diplomacy are closely related in their objectives, analysis, and reporting. The duties of the diplomatic missions include representing the state and safeguarding its essential interests, as well as informing the ministry for foreign affairs about matters of importance. In foreign intelligence, the emphasis is also on lively interaction and monitoring of events in the country of posting, although such activity is characterised by a narrower perspective of national security than that of diplomatic representations’ duties abroad. The new convergence of intelligence and diplomacy has been illustrated, for example, by the sharing of intelligence for public consumption prior and during to the Russian attack on Ukraine. This kind of intelligence sharing, for example for Ukrainian preparedness and unity-building amongst Western countries, is referred to as intelligence diplomacy. However, the transatlantic dimension of intelligence sharing and intelligence diplomacy is being eroded since Trump’s re-election and his pledging allegiance to the red, white, and blue of Putin’s Russia.

Analysis and reporting

Analytical skills are at the heart of both intelligence officers and diplomats. High-quality analysis and timely reporting add significant value to foreign and security policymakers. This added value is enhanced by strategic analysis that anticipates future developments and generates broader conclusions. Information analysed by intelligence officers and diplomats abroad is often further processed in the capital (at the headquarters of the intelligence authority or the ministry for foreign affairs) before being forwarded to the top government management.

The mutual exchange of information between intelligence officers and diplomats is essential. Diplomats support intelligence officers by, for example, providing background and explanations on the leadership and its dynamics in the country of station, on politics and political power struggles, and on current events concerning government plans and actions. Diplomats, in turn, receive important intelligence support, for example, in verifying arms control agreements and in revealing the true intentions of those involved in bilateral or multilateral treaty negotiations. It is not uncommon for new and surprising intelligence to reset the diplomatic agenda.

Three categories of collection

The Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations is a codification of centuries of customary law. According to Article 3(1d) of the Convention, the functions of a diplomatic mission include “Ascertaining by all lawful means conditions and developments in the receiving state, and reporting thereon to the Government of the sending state”. The requirement to obtain information lawfully in the state of deployment also extends to those engaged in foreign intelligence activities when they act as members of the staff of the mission, enjoying almost total immunity from the jurisdiction of the receiving state.

Information collection of foreign intelligence can be legally structured into three categories, of which defence attachés constitute a clearly distinguishable function and category of staff in the diplomatic mission. In organisational terms, defence attachés are part of the military intelligence system. One of the tasks of defence attachés is to acquire information on their host state’s security policy and armed forces and report on these to the Command of the Defence Forces. They are, of course, in contact with the military authorities in the host state and their counterparts from other states. Information collection by defence attachés is open and in compliance with the diplomatic culture. The actual role of the defence attachés is known to the receiving state.

The second form of foreign intelligence is based on international cooperation. Even the exchange of intelligence with foreign intelligence services would be a questionable form of cooperation for a defence attaché not to mention participation in a joint intelligence operation with the authorities of a host state. The latter would clearly be inappropriate for the role of the defence attaché. Such a joint operation, which may involve, for example, extended surveillance, undercover activities, or the installation of a device, or software, is the job for plain-clothes intelligence officers, whether civilian or military.

Given the agreed nature of intelligence cooperation with the authorities of the host state and the fact that the intelligence officer must explicitly respect the limitations and conditions imposed by the host state on the use of the information-gathering method, this is also in line with the Vienna Convention. When an intelligence officer abroad is making general observations, communicating with representatives and citizens of the host state and otherwise acting within the framework of the provisions on international cooperation, he or she may act as a member of the diplomatic staff of the mission. The actual role of such an intelligence officer may not be known by the host state, but his or her appointment, arrival and final departure are.

The last category concerns foreign intelligence and the use of information-gathering methods without the knowledge of the authorities of the state of operation. Such clandestine and covert information gathering can easily violate the Vienna Convention and should therefore, strictly speaking, be conducted outside the diplomatic mission. An intelligence officer who does not enjoy the immunity of a diplomatic agent is ‘fair game’ if he or she becomes exposed: That officer can be arrested and is subject to the criminal jurisdiction of the state of operation, whether just or demonstrative, unless the fate is even worse. Because of these risks and foreign policy sensitivities, the decision to conduct intelligence and use information-gathering methods abroad is often taken by the head of the intelligence agency. If the worst comes to the worst, the Intelligence Director is expected to fall on the sword to protect more important institutions and the executive elite.

Conclusions

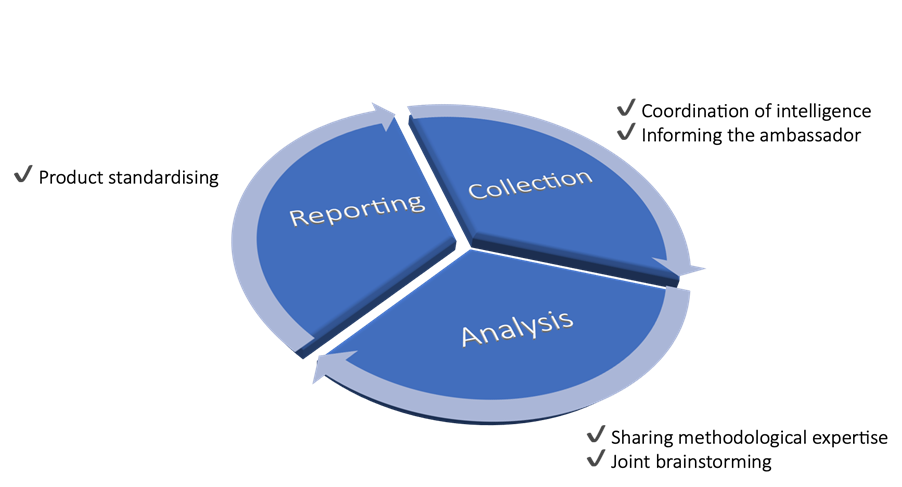

Intelligence and diplomacy most closely link in the phases of analysis and reporting. These final stages of the intelligence cycle offer opportunities for joint work and synergies. This can mean sharing analytical methodological expertise, working through the issues in a brainstorming session for intelligence officers and diplomats, or product standardising.

Information collection is the most obvious extension of diplomacy. The information gathering by the defence attachés, and especially by other civilian and military intelligence officers who operate less openly, adds both content and methodology to what and how diplomats acquire information in their state of accreditation.

At the same time, foreign intelligence operations and the use of information-gathering methods carry risks which, if they materialise, may have repercussions for diplomats in terms of restoring international relations, regardless of whether the intelligence activity is carried out within or outside the diplomatic mission. The fact that intelligence activities are coordinated in advance in the capital does not prevent these risks from materialising. It is therefore important that the head of embassy or roving ambassador is kept informed of planned intelligence operations in his or her mission territory.

The conclusions are presented below in the form of a segmented pie and in the order of a simplified intelligence cycle.