Many traditional oversight mechanisms are reaching their limits in the age of digital, transnational surveillance. How can we close the gap between high-tech intelligence techniques and low-tech and inefficient oversight processes? In our new report, we present seven ideas for data-driven supervisory tools that emerged from the collaborative process of the European Intelligence Oversight Network.

Intelligence collection has always been a tech-savvy business. In very few other fields of government activity can one witness an equally high propensity to develop and adopt new tools and applications at such a fast pace. By contrast, traditional accountability mechanisms and review processes often struggle to keep up with this rapid evolution of surveillance technologies. As a result, the bodies tasked with reviewing the activities of intelligence agencies may struggle to effectively enforce the protection of civil liberties and privacy. This, in turn, also undermines the democratic legitimacy of the agencies.

There is a growing awareness among many European oversight bodies that their current toolkit needs an update. In December 2019, 18 oversight bodies from 16 countries gathered at a conference in the Hague to discuss how “to adjust and innovate to keep up with the advancement of technology”. The increasing volumes of data that intelligence agencies need to wade through — due to larger troves of data collected by them, more data sources being available, and the inexpensive duplication of data — lead to a greater demand for data analysis tools with which to make sense of them. The sheer amount of data that requires review, paired with the advanced technology used by the agencies to interpret them, overwhelm existing legal guarantees and effective oversight. Against this backdrop of information overload, establishing detailed legal rules and guidelines that stipulate how to collect and analyse data is not the end, but rather the beginning of meaningful intelligence governance. As in many other policy fields, from food safety to aviation, laws must be implemented and enforced with the help of modern, robust oversight.

Tech-enabled intelligence oversight has been inconclusively debated for too long

The call for oversight innovation is not a new one. There have been various collective efforts to discuss challenges and share best practices, such as the recent conference in The Hague mentioned above or a cooperation of six European oversight bodies. Moreover, a number of oversight bodies have recently implemented budget increases and hired additional staff. Still, there remains a stark discrepancy between the security sector on the one hand and the accountability and oversight landscape on the other as far as investment in, and application of, technology is concerned. To contribute to the discussion on oversight innovation, we drafted an ambitious programme for implementing supervisory technology and more effective oversight instruments. Developed with advice from the European Intelligence Oversight Network (EION), we propose seven tools to move from paper-driven to data-driven oversight, each representing a response to a concrete oversight deficit. In the following, we will highlight some of them.

Audit trails for data processing

Modern data analysis entails numerous risks in terms of data abuse. For example, a declassified ruling of the U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) showed how the FBI misused the NSA’s bulk surveillance data by looking up online communications of U.S. citizens, including those of FBI employees and their family members. This is also a problem in other security sectors, such as policing where cases of officers querying sensitive personal information for private purposes are regularly reported (see a collection of cases in the UK and Germany).

Analysing log files is an important tool both for internal compliance units as well as for independent oversight bodies. Log files provide granular information about when, how, how long, and by whom a given computer system is used. With the help of data analysis software, reviewers can track and visualise relevant statistics and patterns that reveal “normal” use and outliers such as particularly high frequencies of queries for a given file, unusual activity of individual users, or exceptional access times.

Over time, oversight bodies can also detect outliers in the statistical patterns contained in log files. For instance, deletion records enable better monitoring of retention limits and allow to track suspicious peaks of data destruction. Data deletion is typically an automated process, thus manual purging of files should encourage further inspection of the event (e.g. the infamous “Operation Konfetti” of the German domestic intelligence agency). Access to logging data can also be used to set up automated “alerts” that flag especially critical data sharing activities for in-depth review by the competent oversight bodies.

Independent auditing of data filtering

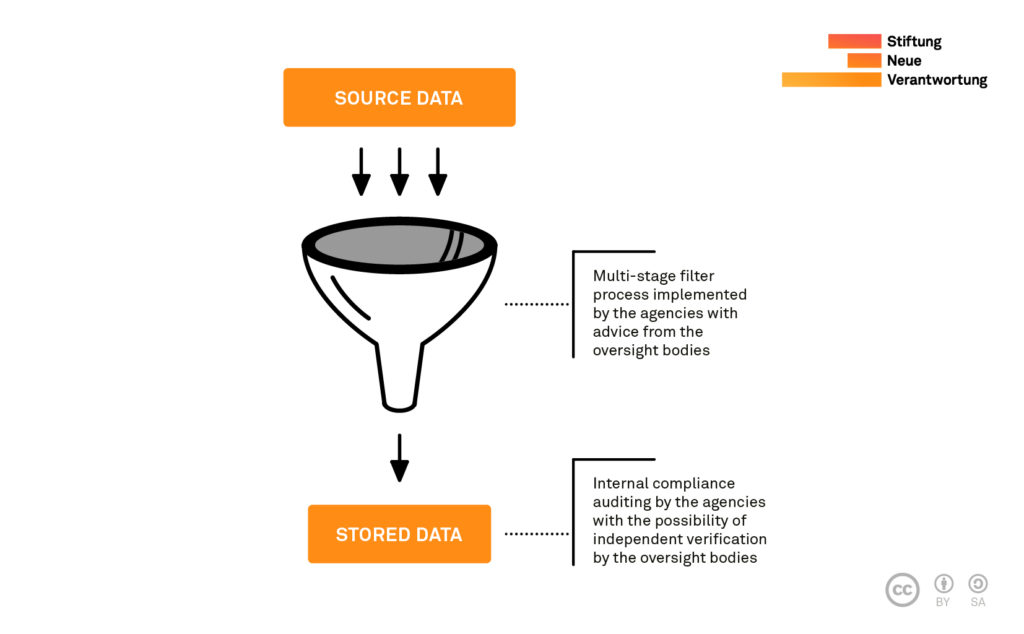

Agencies carry out very complex data reduction processes, by which the vast amounts of data collected are filtered through a set of parameters, such as location, keywords of operational relevance, or privileged communication (e.g. between journalists and sources or clients and lawyers). The latter is critical for legal compliance. However, these filters are rarely submitted for independent checks for precision and reliability. Direct access to the services’ stored data enables oversight bodies to test the accuracy of the data filtering process. This includes scanning the databases for identifiers (such as phone numbers) that should not be detectable in the filtered data.

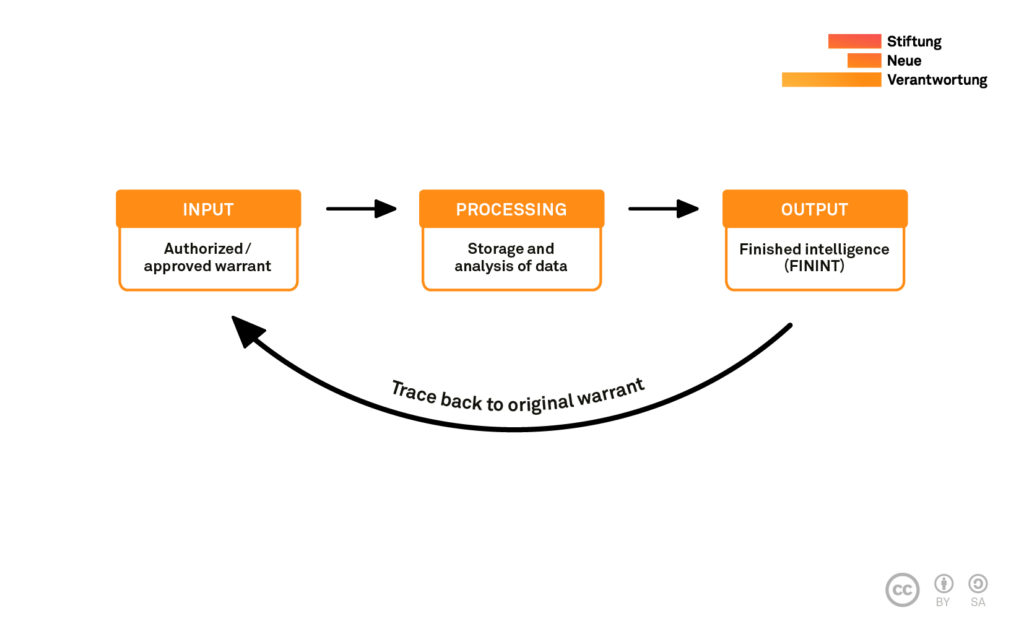

Tracking the use of surveillance authorisations

Some oversight bodies have to cope with large volumes of requests for surveillance measures; for example, the French oversight body CNCTR provided over 73,000 opinions across all intelligence collection methods in 2018 alone. How do oversight bodies keep abreast of so many warrants when deciding on the necessity of new applications? An informed decision about a new warrant should take the existing authorisations and their implementation into account. There may be cases in which a government applies for a large number of measures and, upon their approval, decides to only act upon a few of them.

Thoroughly tagging data origins (in the services’ operational systems) allows oversight bodies to trace back a given dataset or intelligence report to a specific warrant. Such documentation then enables authorising judges to detect the simultaneous use of multiple surveillance measures and make a better informed assessment of the necessity of new requests.

Procedural safeguards to complement digital instruments

Of course, not all innovations must or should be tech-enabled tools. Sound procedural safeguards should accompany the use of technical applications. Risk assessments are an analogue but equally important tool to prioritise oversight tasks. Arguably, most countries can improve how they pursue the question of where to invest limited time and resources. Risk assessments are a systematic approach to planning oversight activities. This includes calculating risk scores for specific operational systems that the intelligence services use, which helps the overseers to determine the resources and types of inspections that will be needed for review. The Danish oversight body TET is already using a risk assessment approach in order to map the diverse storage locations, devices, IT systems, and software tools that the services use to collect, retain, and analyse data.

Oversight-carrier dialogues are another process-focused method that allows to detect potential overcollection at interception points. Some types of warrants for bulk data collection can be extremely broad, leaving a huge leeway for implementation. Some oversight bodies have therefore already established direct relationships with internet service providers (or postal operators, mobile network operators, communication service providers, etc.). These ties should be expanded to establish robust, direct communication channels between service providers that route or store relevant data. In conjunction with mandatory error reporting, such routine exchange formats complement other data-driven oversight tools.

Towards an oversight-by-design principle

There has been an overreliance on purely legal solutions to tech-inflicted challenges for too long. Our report shows that many legal requirements cannot be effectively enforced if the corresponding practical measures are not taken.

Data-driven instruments are key to filling some of the oversight gaps. All stakeholders can contribute to addressing current oversight challenges. It is in the interest of intelligence services to guarantee that their processes and information systems are designed to be overseen in a sensible and efficient manner. Ensuring accountability relies on actual overseeability across all phases of the agencies’ data processing. This includes providing direct access to the operational systems and databases used by the intelligence services that some oversight bodies already enjoy. What is more, detailed log files must be made accessible in a format that allows for more granular reviews and verification.

Time for a system update

This article only provided a glimpse into the wealth of tools and ideas from various sectors that intelligence oversight could benefit from. Much can be learned from established practices in to support audit tasks(e.g. finance auditing or corporate compliance) when it comes to detecting suspicious use patterns in log files.

These tools ought to inform a context-specific agenda for more effective intelligence oversight. This is best achieved if all relevant stakeholders in a given country engage in open dialogue. The needs of oversight bodies (such as specialised surveillance courts and data protection authorities) must be taken into account already during the construction of intelligence agencies’ operational systems. The French intelligence framework, for example, demands early-stage advice from the oversight body CNCTR on the services’ data-tagging processes.

Governments, agencies, and oversight bodies all stand to benefit from more effective oversight instruments. For instance, oversight bodies’ access to robust audit trails may reduce the reporting costs for intelligence services. If overseers automatically receive relevant and complete logging data that allow for efficient auditing, resources are freed up for both the overseers and the overseen.

That said, supervisory technology should not be regarded as a substitute for traditional, manual oversight mechanisms. On the contrary, they should be seen as necessary additions to existing toolkits and inspection processes in the age of digital surveillance. Done right, and drawing on the input of all relevant stakeholders, data-driven innovations and supervisory technology enable oversight to be more proactive and improve the explainability of oversight decisions. It is important that reviewers embrace new oversight tools — not as a replacement for their work but as a powerful addition that will allow them to work more effectively.