Germany has yet again changed its legal framework for foreign intelligence collection in March 2021. The new law expands Germany’s SIGINT powers and allows it to hack foreign ISPs. Out of the many complex new rules and regulations, we highlight five features of the amended BND Act ranging from unrestrained metadata collection to broad testing capabilities and new basic protections for press freedom.

Previously on German foreign intelligence reform:

- 2016 first post-Snowden BND reform

- 2020 landmark constitutional court judgement

- 2020 pre-legislative scrutiny proceedings

- 2021 second BND reform

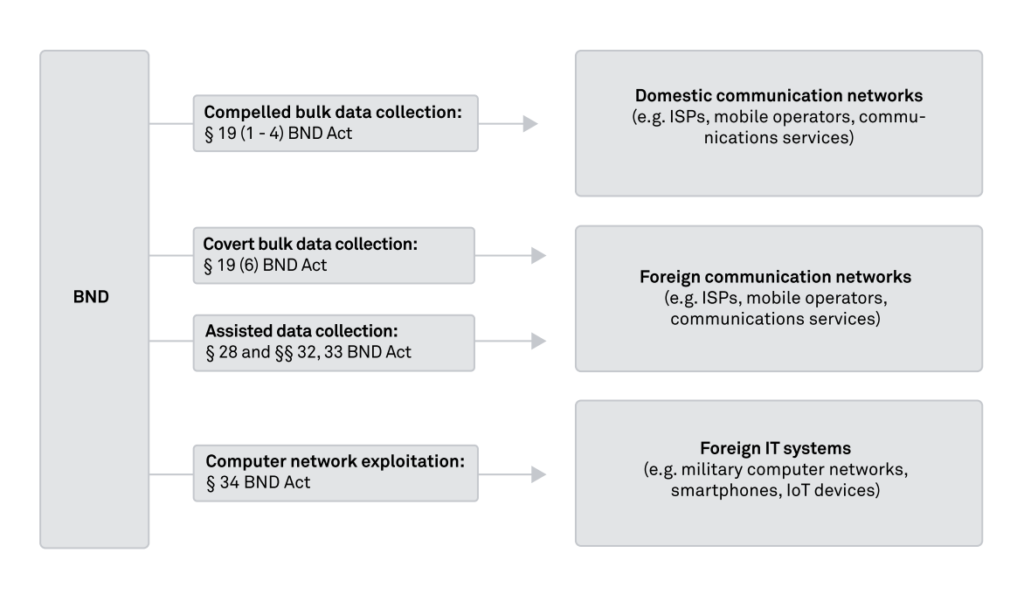

The latest, but by no means last, episode in Germany‘s SIGINT policy-making process resulted in the Bundestag’s adoption of a whole new set of complex provisions and exceptions. It is easy to get lost in the intricacies and cross references of the amended Act of 2021. It is now (mostly) in force and includes an expanded mandate for strategic bulk interception, computer network exploitation and transnational data sharing of Germany’s foreign intelligence agency, the BND (see our in-depth analysis here).

Most democracies deploy methods of strategic surveillance of communications to gather foreign intelligence. Yet only a small minority of democratic states placed such powers under a genuine legal framework, adopted by parliament and not by the executive. The new German SIGINT law, thus, deserves careful scrutiny by the international community because it presents a rare opportunity to learn about the contemporary practice of bulk collection and dissect how controversial surveillance practices and data transfers with numerous extraterritorial ramifications are regulated and overseen.

Below, we highlight five (out of many other important) aspects that we think you should take away from Germany’s latest reform of its legal framework for bulk collection:

#1 The new legal basis officially allows to hack foreign ISPs

If the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND) wants to collect foreign communications from a mobile network or internet service provider (ISP) based in Germany, it may legally compel the company to cooperate and facilitate access to the required data. But what about accessing data from communications providers that are not subject to German jurisdiction? Naturally, the data held by foreign providers is often of great interest to the BND, considering that its mission is to collect relevant information about foreign and security policy around the globe. As the German SIGINT agency cannot legally compel a foreign company that holds or routes the data to provide access, the new legal basis now explicitly allows the BND to secretly infiltrate foreign providers. Thus, provided the legal requirements listed in the BND Act are met, the law now provides a formal mandate for the BND to hack into the IT systems of, for example, a telecommunications network in India to covertly gain access to foreign communications data there.

In addition, the BND now wields a comprehensive legal authority to interfere with and exploit foreign computer systems. Pursuant to this (bulk) equipment interference power, the BND may infiltrate any IT system abroad that it expects to yield relevant intelligence information in line with its lawful aims.

Overview of the BND’s foreign surveillance powers (more details)

Statutorily authorizing one’s intelligence agency to break into the computer systems in a foreign country will likely come into conflict with the domestic law of the state targeted by such a measure. Nonetheless, German lawmakers considered these surveillance powers to be necessary to protect Germany’s security and its capacity to act in international relations. To date, only very few countries have legal frameworks, let alone laws that openly express the will of the people, on such covert interference abroad.

#2 Bulk collection of foreign metadata remains unrestrained

Due to the large volumes of data processed, the collection and analysis of metadata, such as traffic data or related communications data, is crucial to gather foreign intelligence with bulk collection methods. In its Grand Chamber decision on the Swedish SIGINT framework, which was handed down after the BND Act was amended, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), thus, considered that the collection of metadata “should be analysed by reference to the same safeguards as those applicable to content.”

The amended BND Act does not, however, provide any safeguards for the collection of foreign metadata. Instead, it allows for the unrestricted collection of supposedly “non-personal” metadata, which includes foreigners’ traffic data.

While the ECtHR acknowledged that the collection, retention and processing of bulk metadata is highly intrusive, the amended German bulk interception regime offers no protection for foreign metadata. This disconnect with the ECtHR’s criteria might trigger new litigation, given that it may have chilling effects on the exercise of fundamental freedoms, such as press freedom, around the globe.

#3 Automated filters shall enforce basic legal requirements without independent oversight

According to its own testimony during the proceedings before the Constitutional Court, the BND deploys between 100.000 and 999.000 search terms simultaneously to collect personal content data, such as text messages or phone calls. Between 50 and 60 percent of search terms used by the BND stem from intelligence services of allied states.

How can the BND ensure compliance with legal requirements, given the large scale and deep transnational entanglement of its SIGINT operations? The law prescribes the use of automated filter systems to scan whether intercepted data includes information on, for example, personal data on German residents or protected confidential communications.

Regarding the sharing of protected professional communications, the BND must maintain block lists of identifiers of journalists, lawyers and clerics whose communications are afforded special protection in order to gradually improve the filter accuracy. Creating such block lists to automatically reject data related to protected groups was an explicit requirement by the German Constitutional Court judgement. The accuracy of the filter systems must be subject to random checks by internal BND staff. According to the BND, about 300 search terms are checked manually per month (recall that a six-digit number of search terms is in use synchronously).

Despite frequent calls to the contrary by observers from civil society, the current law does not foresee an active involvement of the independent oversight body in the filter verification. Only the Chancellery must be informed every six months about the BND’s manual random inspections.

#4 Warrantless use of bulk collection for testing purposes dodges the independent authorization mechanism

Like other foreign intelligence agencies, the BND may perform so-called suitability tests (Eignungsprüfungen in German) in order to either test the suitability of specific telecommunication networks for bulk collection purposes or to generate new search terms and assess the relevance of existing search terms.

Suitability testing is meant to ensure that bulk collection is targeted at the most relevant carriers, using the most appropriate search terms. Yet, if the BND deploys suitability tests in pursuit of relevant search terms, no legal safeguards, such as independent ex ante authorization based on warrants are required.

What is more, there is no limit for the duration and the volume of data collection for testing purposes. Importantly, the BND may also transmit data from suitability tests automatically (i.e., without further data minimization) to the German Armed Forces where the requirements that regulate the use and transfers of such bulk data are far less stringent and transparent, and not subject to effective judicial oversight.

The limits and protections that apply to bulk data collection have little value if the mandate for suitability testing is too permissive and escapes independent approval and oversight. We doubt that the provision whereby service providers can be compelled to assist with suitability tests can be considered within the limits of what is strictly necessary and thus justified in a democratic society. Rather, one could regard this as an unduly broad obligation on the part of service providers to transmit data to intelligence agencies “by means of general and indiscriminate transmission” as the CJEU has put it in its Privacy International judgement.

#5 The confidential communications of foreign journalists, lawyers and clerics shall not be surveilled

The BND Act now offers some requirements for how SIGINT programs must protect certain professional communications: In principle, the BND may not collect personal content data or infiltrate devices if they relate to the confidential communications of clerics, lawyers and journalists.

However, the law includes exceptions to this general rule. For example, when facts justify the assumption that a person from one of the three professional groups is the perpetrator or participant in certain criminal offenses, the collection of related confidential communications or the hacking of computer systems is legally permitted. The same is the case if the data collection is necessary to prevent serious threats to life, limb or freedom of a person and a number of other legal interests (paragraph 21 section 2 of the BND Act, in German).

Thus, the new legal norm requires two complex weighting decisions: Firstly, the BND needs to assess whether a person belongs to one of the three protected professional groups. Which communications actually qualify as protected confidential communications is a complex assessment that is made exclusively by the BND.

Secondly, then, the BND needs to weigh if there are facts that would still allow exceptional data collection of these confidential relationships. For example, in which cases would it be justified to monitor the confidential communications between a journalist and a source or of a priest who counsels a believer on the phone? The law foresees a mandatory ex ante approval of lawfulness by the judicial oversight body for such balancing decisions on legal exceptions to the protection of professional communications.

Notably, this judicial authorization power also extends to international data transfers. For instance, the sharing of a lawyer’s personal communications data would be allowed if evidence justifies the suspicion that he or she may be the perpetrator or participant in a crime (paragraph 29 section 8 of the BND Act, in German).

Not yet caught in the Act?

The 2021 overhaul of the legal framework for German foreign intelligence collection too frequently entails legal loopholes and gray zones that weaken effective intelligence accountability.

If you want to dive deeper, our research report makes concrete recommendations to enhance the quality of the legal basis and address some of the deficits. It also provides more context for the different investigatory powers available to the BND and the new oversight regime.